Art

Qalbi

Ittri lilu nnifsu, Dinjiet għalina: Is-Surrealiżmu Animat ta' Obi Agwam

Kliem minn Teneshia Carr

Wara nofsinhar nitkellmu, Obi Agwam għadu kif ħareġ mit-Tube u fl-istudjo tiegħu f'Londra. Huwa ftit dazed, kontinwament yawning, taħt il-kaffeina, u, kif jirriżulta, bil-kwiet jiċċelebra għeluq is-26 sena tiegħu. "Għadni kemm wasalt fl-ispazju tal-istudjo tiegħi lanqas żewġ minuti ilu," jidħaq. "Jien hawn għal madwar sena." Iċ-ċaqliq minn Queens għall-programm prestiġjuż ta’ fellowship tar-Royal Academy huwa aċċelerazzjoni selvaġġa bi kwalunkwe miżura. Iżda għal Agwam, il-veloċità ta 'dan kollu hija inqas dwar ix-xorti u aktar dwar iċ-ċarezza.

Imwieled f'Lagos u trabba f'Southside Ġamajka, Queens, Agwam trabba f'dinja li kienet kemm iper-viva kif ukoll ikkontrollata ħafna. Il-ġenituri tiegħu żammewh ġewwa għas-sigurtà, imma l-belt għallmitlu l-indipendenza kmieni. "Kont fuq il-ferrovija kmieni kemm bħal 10, 11 snin," jgħid hu. "Trid tikseb dawk il-ħiliet reali kmieni—li tkun responsabbli, ivvjaġġar, tkun sigura u konxja." Ġewwa l-appartament, ir-rotta tal-ħarba kienet tfassal. B'aċċess limitat għad-dinja ta 'barra, ħabb għall-kartuns u l-animazzjoni. Universi alternattivi li ħassew isbaħ minn dak dritt barra t-tieqa tiegħu.

"Bdejt niġbed mid-dwejjaq," jiftakar. "L-inħawi fiżiku tiegħi ma kienx partikolarment stimulanti, imma l-cartoons offrew livell ta’ ferħ li ma kontx nakkwista b’mod naturali. So I istantanjament tip ta 'użu bħala mekkaniżmu biex ilaħħqu." Dik "mekkaniżmu li jlaħħaq" bil-kwiet bnew pedament: it-tifel li jista’ jiġbed fil-klassi, l-adoloxxenti doodle f'notebooks, l-artist żagħżugħ li għadu ma rax l-arti bħala triq tal-ħajja vijabbli.

Dik il-bidla ma waslitx qabel kulleġġ komunitarju, wara li l-Universitajiet li ried inizjalment qalu le. "Ġegħluni nixtri l-ewwel żebgħa tiegħi," jgħid dwar kors introduttorju tal-pittura. "Qabel dan, Jien dejjem kont qed npinġi... Kienet biss xi ħaġa biex tgħaddi l-ħin. F'dik il-klassi, sfurzawni noħloq xogħol ta’ l-arti b’mod fiżiku, ,mod tanġibbli, fuq tila. U minn dik is-sena, Għadni kemm bdejt nagħmel l-affarijiet."

2019 kien il-bidu. 2020 kienet il-pandemija—aċċess ta’ 24 siegħa għall-immaġinazzjoni tiegħu stess. "Aħna msakkra ġewwa. M'għandix x'nagħmel," hu shrugs. "Allura aħna se żebgħa." Beda jpoġġi x-xogħol fuq l-internet mingħajr pjan, konsistenza biss. Fi żmien sena, kellu udjenza; minn 2021, kien qed juri fil-galleriji fi New York, Los Angeles, u Londra. Fi 2024, hu tella’ l-ewwel spettaklu waħdu tiegħu f’Harkawik f’Manhattan. Issa, l-Akkademja Rjali.

Jekk il-kronoloġija tinstema' improbabbli, Agwam huwa l-ewwel li jirreżisti l-leġġenda ta 'skoperta f'daqqa. "Jien nemmen fid-destin," jgħid hu, "imma nemmen ukoll li n-nies jgħidu tagħhom dwar dak li hu maħsub għalihom. In-nies dejjem jgħidu, 'Jekk huwa maħsub li jkun, huwa maħsub li jkun,' imma naħseb li għandna l-aġenzija tagħna stess. Naħseb bil-mentalità t-tajba, Jien nista’ nkun artist illum, tabib għada, astronawta l-għada. B'biżżejjed ċarezza u fokus u intenzjoni, Naħseb li kollox huwa possibbli."

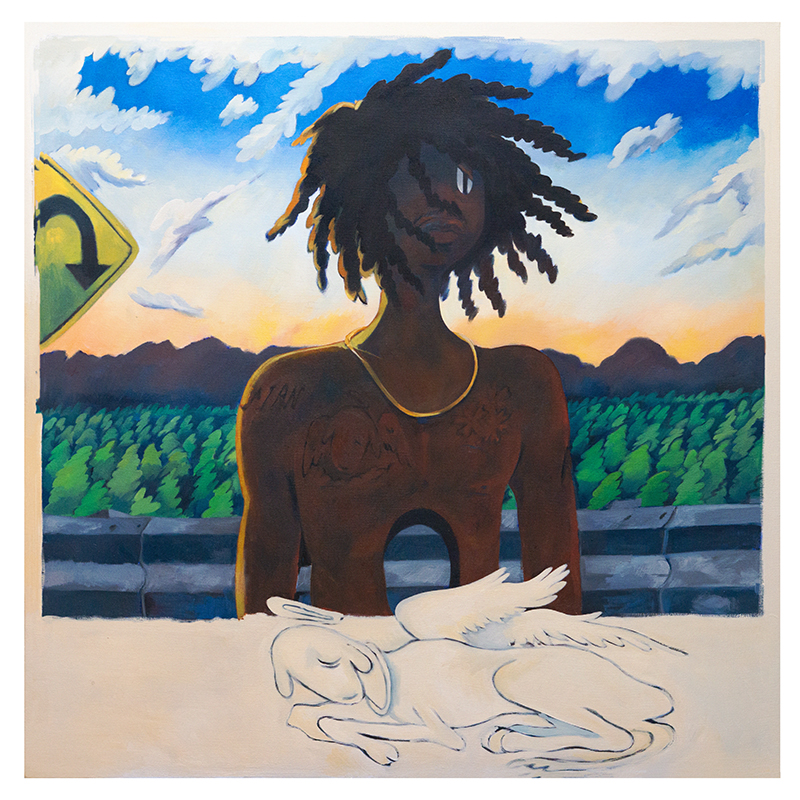

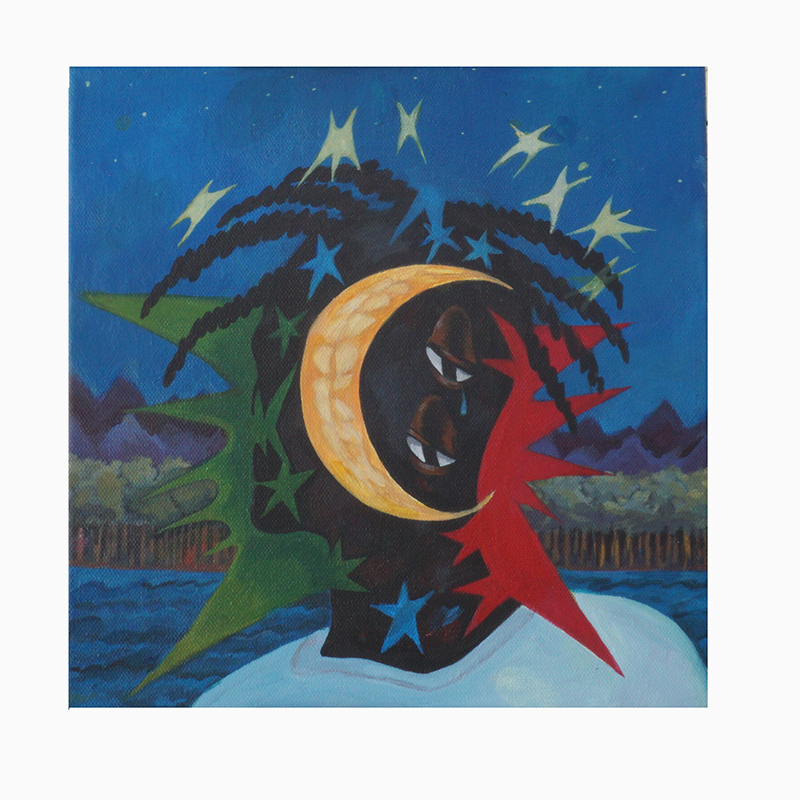

Dak it-twemmin fl-aġenzija jidher fix-xogħol innifsu—pitturi popolati minn elastiċi, figuri animati li donnhom iduru xi mkien bejn il-kartuns, spirtu, u memorja. Ix-xbihat tiegħu jħoss bħal ħolma tad-deni ta’ Blackness: riġlejn imġebbda, espressjonijiet tal-gomma, Dinjiet li jivvibraw bil-kulur u storja kkodifikati. "Nixgħel fil-fantasija u s-surrealiżmu u l-immaġinazzjoni," jispjega. "L-immaġinazzjoni sservi ħafna skopijiet differenti. Huwa jservi skop fl-att ta 'reżistenza. Huwa jservi skop fl-awto-serħan il-moħħ u sempliċement tħossok aħjar. Jekk id-dinja qed tiġnun u d-dinja fiżika tiegħek qed tisfar jew le dak li trid, l-aqwa ħaġa li jmiss hija li timmaġina d-dinja barra minnha."

Għalija, dik id-dinja immaġina hija marbuta ħafna mal-figura Iswed u n-nisel viżwali mimli li ġġorr. Jgħaddas fl-animazzjoni Amerikana tal-bidu tas-seklu għoxrin, Karikaturi ta' l-era ta' Jim Crow, razzista u grottesk, u jolqothom ma’ cartoons kontemporanji u artab, forom barranin. "Fl-1920s, 30s, u 40s u 'l quddiem, In-nies suwed kienu deskritti b'ċertu mod, l-aktar jilagħbu fuq sterjotipi," jgħid hu. "Allura nixtieq nieħu xi wħud mill-elementi viżwali minn dak, u ħallathom ukoll ma’ elementi viżwali minn cartoons moderni u rappreżentazzjonijiet inqas offensivi ta’ figuri Iswed. Jien ħafna, ħafna, imħasseb ħafna li jnaqqas id-distakk bejn xi ħaġa li hija illustrattiva u iblah u divertenti, u xi ħaġa serja, arti għolja."

Iċ-ċifri tiegħu ma jimmirawx għar-realiżmu. Huma jimmiraw għas-sensazzjoni. "M'għandux għalfejn ikun iper-realistiku. Mhux dejjem irid ikun ta’ osservazzjoni," jinsisti. "Dejjem ħassejt li qed inpinġi b'mod astratt kif inħossni tħoss il-ħajja Iswed, aktar milli kif tidher il-ħajja Iswed."

Dik id-distinzjoni hija importanti. Fl-univers ta’ Agwam, il-figura Iswed titħalla tkun elastika, stramb, ecstatic, melankoniku, u meħlusa mill-piż tal-leġibilità. Il-pitturi jaħdmu mhux biss bħala stampi iżda bħala ittri. Huwa ġurnali, timmedita fuq memorji speċifiċi, u juża dawk it-testi bħala prompts għal kull biċċa. Dejjem aktar, il-kliem innifishom infiltraw fil-wiċċ: envelops ittimbrati, linji miktuba bl-idejn, frammenti ta’ korrispondenza. "Dawn ir-ritratti huma bħal ittri lili nnifsi u mbagħad ittri lil min qed jaqrah," jgħid hu. "Huwa bħall-memorja, animazzjoni, immaġinazzjoni li tidħol f'dan il-pot tat-tidwib kbir."

Hemm ukoll qlubija aktar kwieta fil-mod kif jinnaviga r-riskju. Agwam huwa konxju sew tal-linja fina bejn ir-rikjesta tal-karikatura u r-riproduzzjoni tal-ħsara. "Hija linja rqiqa bejn xogħol artistiku offensiv u mhux offensiv," huwa jirrikonoxxi. "Naħseb li ssib bilanċ billi tipprova u billi tfalli. M'inix kuntent ħafna bil-biċċa l-kbira tax-xogħlijiet tal-arti li nagħmel, imma xorta waħda poġġih barra. Għax kultant kif inħossni huwa irrilevanti għal kif in-nies l-oħra ser iħossuhom dwarha."

Aqra aktar fi Ħruġ 33