Art

GISELA MCDANIEL

Healing through Art

Gisela McDaniel

Words by Matthew Burgos

Images Courtesy of artists and Pilar Corrias Gallery in London

One's journey towards healing may lead them away from the person they were before. The tremors of change shift perception and transform the person, shedding the old skin in layers. "Healing is not linear. You are not going from point A to point B, from wounded to completely healed. It is a transformation. You will never be the exact same person you were. It is a part of you, but it does not need to become you. You grow and become a more complex, informed, and, hopefully, stronger person. I wish the world we lived in did not require people to learn how to be resilient to survive." These powerful words from artist Gisela McDaniel speak to a person accepting loss while focusing on self-discovery.

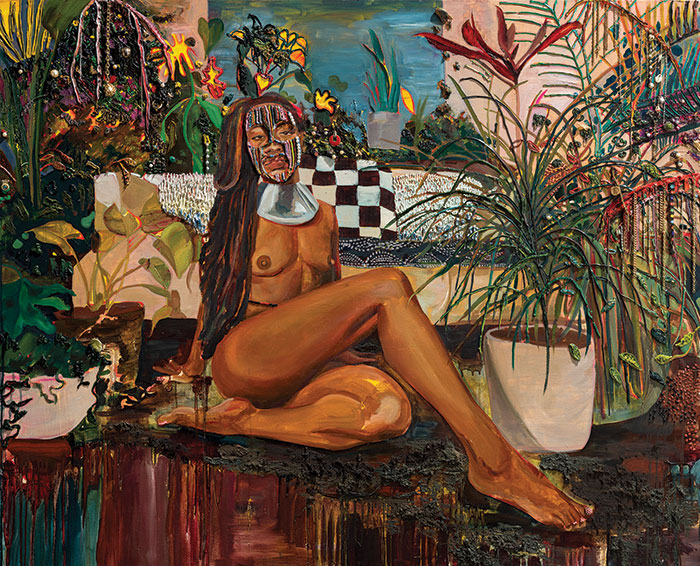

A view of the artist's studio displays blotches of black and white paint draping the cemented floor and canvasses of varying sizes, either hanging or reclining on a white wall. As one walks closer to the paintings to scrutinize their earthy tones and personal histories, you find people who identify themselves as women, non-binary, indigenous, multiracial, immigrants. They are kneeling or lying down on a carpet or an apartment's floor, a jungle-like background looming over their bodies. A diasporic, indigenous Chamorro artist based in Detroit, McDaniel's practice in art employs social research, oil portraiture, identity in diaspora, and motion-sensor technology. "Art has always been my first language and form of communication. I remember seeing an impressionist painting by Monet somewhere and being so mesmerized by the scene that sharpened and softened as I moved forward and backward. I was so fascinated by the fact that I could see where the artist made marks and thought: I can do that too."

As her art narrates bodies, voices, and stories of women and non-binary people, it crafts a solace to those who have survived gender-based sexual violence. It is a personal vehicle for the survivors to voice their experiences and how that violence has affected them. As a survivor herself, McDaniel understands and allows her subjects varying degrees of anonymity once she paints their chronicles. "I begin my painting during the initial conversation I have with the subject and end it when the masks are added to the painting, as well as placing their voice in the space of the canvas. My process begins in an intimate and private space, then I gradually apply protective layers until it is ready to be shared in a public space or exhibition." During the conversation between her and her subjects, she places a recorder between them and asks them about their most significant objects, the symbols of who they were, and how they are. By collaborating with the subjects, a sense of control is given back to them as they steer the ship of how they are represented. They decide on the space and with what objects and positioning to regain autonomy and privacy.

Viewing the paintings anchors only a portion of the voyage to understanding the history behind the art. McDaniel operates with motion-sensor technology to immerse her audience into her artworks, placing them in the subjects' shoes and their experiences. The paintings come to life as they talk back to the audience once the latter triggers the sensor. As McDaniel tells Blanc, "the audio is in place to release the person from the responsibility of carrying their story alone. So many people experience sexualized violence. I hope to put these stories into the world, so survivors are not the only ones responsible for dealing with this issue. Violence against women and femme-identifying people is a global issue that has been present throughout history and colonization. Story sharing is a critical process, a dialogue, that allows a shared perspective to emerge and enables movement towards solutions that will ultimately make the world safer for everyone. I choose to work with motion sensors as they create a physical boundary for the painting: you cannot step into the painting's personal space without interacting with the story, just as you would interact with a person. It asks the viewer to consider someone's circumstance and treat them with respect, which I believe is the bare minimum, yet some people need to be reminded of."

When asked about a painting she has worked on that mirrors who she is as an individual and an artist, McDaniel shares "Cleveland: Where She Went/What She Saw honors and tells the story of three generations of Navajo (Diné) women. We recorded the story of the eldest, who moved from the reservation in Arizona to secretary school in Cleveland, Ohio, before turning to the youngest on her pursuit of reclamation of their traditions." The three women sit on a sofa. Significant symbolisms pepper the canvas, such as a vintage wallet-size portrait, a string of sea-blue beads resembling the woman's necklace on the right, and pressed flowers and pieces of jewelry over a beach-like setting.

"I have been thinking about transformation often and how all the events in our lives, every person and moment we meet, transform us. I absolutely think transformation is inevitable and necessary. The world around is always changing, and we must adapt to survive and to be better for each other. As our world and technology grow and develop, it is our ethical responsibility to transform spiritually and make sure we still care for the land and people around us. There are so many ways to think about metamorphosis, but it is necessary to foster care and empathy in the world as we undergo so much. We must fight for safety, equity, and empathy for all as the world sheds its outdated and often unfair systems. We are very much in the midst of change; we must embrace it and lean in without forgetting who we are and where we come from." In Gisela McDaniel's metamorphosis, she dusts off the shells of her cocoon, flies to the edge of the cliff, and soars high to narrate her community's healing through art.